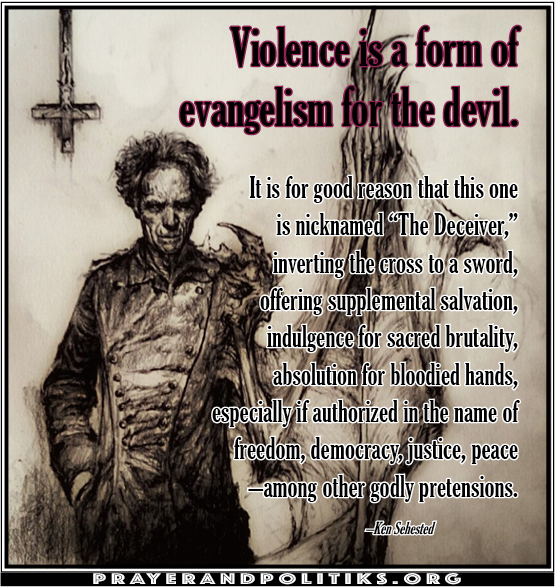

Violence is evangelism for the Devil

by Ken Sehested

My earliest memory of Memorial Day is of my Dad, puttering in his garage shop (he was a mechanic and jack-of-all-trades fixer-upper) on a rare day off from work, listing to the Indianapolis 500 car race on a portable radio. On one of those occasions I remember using a hammer, and the concrete garage floor, helping him straighten nails for reuse.

Both my parents were children of the Depression. Thrift was a primal virtue even when it was no longer a necessity.

I have no doubt Dad would silently recall some of his war-time experience while enduring the monotony of listening to race cars doing 200 laps around an oval track at speeds in excess of 200 mph. He managed to survive being in the first wave of troops landing at Omaha Beach in the 1944 D-Day invasion of Europe, though I can remember only once in my life when he talked about those days. I was an adult before I knew he carried a bit of 88mm German artillery shrapnel, bone-embedded, behind his right ear.

There’s no doubt he suffered what we now call post-traumatic stress syndrome. Though an uncommonly a kind, generous man, I grew up learning to anticipate circumstances that could provoke inexplicable outbursts of rage.

I inherited two memorable treasures from Dad’s days as a combat engineer. One is a “Shield” New Testament—which literally has a metal front cover engraved with the phrase “May this keep your life from harm,” given to him by one of his sisters before he shipped overseas. The other was a P-38 German officer’s pistol, which looks very much like the more famous “Lugar” model. I sold the latter to a gun dealer to help fund a mission project in Cuba.

the latter to a gun dealer to help fund a mission project in Cuba.

Along with the Indy car race, no Memorial Day weekend would be complete without a glut of retail sales, car excursions (over 39 million will drive at least 50 miles this year), and grilled meat (60 million pounds, according to one estimate) to accompany patriotic parades and flower adorning of graves of those who died in our nation’s wars.

The latter moves further from the spotlight each year. Not because the casualties have ceased but because the makeup of our nation’s military is drawn from an increasingly smaller percentage of the population—the majority being refugees from a market economy which siphons wealth from the bottom to the top. Given this circumstance, the reliable pay of military service looks more attractive.

Maybe it gets harder to maintain a Memorial Day focus simply because we have so many of such occasions. Altogether each year we have 14 commemorations which reference our nation’s military prowess.[1]

Nevertheless, with all our fellow citizens, we stand in honor of such sacrifice and in acknowledgment of the grief borne by many.

At the same time, though, the believing community needs to ponder the conflicting memorials which roll around nearly as often as the church gathers around The Lord’s Table, many of which bear the carved inscription featuring King James’ rendition: “This do in remembrance of me.”

Whose remembrance takes center stage?

§ § §

“Greater love has none than this,” Jesus says in John’s Gospel, “than to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (15:13).

Yet with Jesus’ “greater love” affirmation, this question lingers: To what end is life righteously surrendered for the common good? Indeed, there are countless causes powerful enough to inspire martyrdom. Creating mayhem is a popular goal.

We should be forever suspicious of those who praise the greater good and studiously avoid consideration of the common good—and by extension, for people of faith, of the Commonwealth of God.

§ § §

Among the many locales that lay claim to Memorial Day’s origins[2] is Columbus, Mississippi, where on 25 April 1866 four women processed from the city to Friendship Cemetery. One of them suggested that flowers be laid on the graves of all Civil War veterans—Confederate and Union alike—of which there were plenty, since the city had been a hospital town to which trainloads of the wounded and dead from both armies were transported after the massively brutal Battle of Shiloh in western Tennessee.[3]

This, I dare say, is the only proper function of memorial days: to mark the grievous tragedy and squander of war, rather than to glorify its victims, exalt its agents, and indemnify its ongoing execution.

The enduring scandal of the Gospel—even in a land like ours, purportedly “under God” and crowded with spires and steeples—is Jesus’ rejection of redemptive violence. As if God needs a little bloody shove to guarantee Heaven’s saving purpose. The arrogance of such a claim, disguised by the assertion of holy justice, is breathtaking in its design and pursuit.

The community of faith’s claim is not to a higher moral purity than the soldier. In fact, the church should be  jealous of the military’s ability to inspire young men and women to be trained for the day when going into harm’s way, for the sake of something larger than personal safety and private profit, is called for.

jealous of the military’s ability to inspire young men and women to be trained for the day when going into harm’s way, for the sake of something larger than personal safety and private profit, is called for.

The claim made by those rejecting sanctified violence is to a different mandate flowing from an alternative theological vision. Everyone wants peace, of course; none but a minuscule number of sociopaths gleefully promote war. But our dilemma is this: We also want what we cannot get without war.

§ § §

People of the Way remain committed to a peculiar allegiance and a distinctive conviction: that all violence, of every sort, is a form of evangelism for the Devil. Those who stand by this claim get no extra cookies nor receive special privilege. Pride is excluded from the armor of faith, and boasting is limited to the promise that loving enemies is the only fruitful way to lasting peace, in imitation of the one who refused the option of a militarized angelic rescue from the crucifier’s grisly work. (cf. Matthew 26:53)

We make this profession of our faith even knowing that we ourselves are not immune from the lust for vengeance. As César Chávez, the great practitioner of nonviolent struggle for justice, said: “I am a violent man learning to be nonviolent.” Indeed, we are given the grace to confess our bloodlust precisely because we stand in merciful submission to the promise of life that is to come.

The meek are getting ready. And they welcome the company of any with eyes to see and ears to hear Christ’s arising, arousing, and disruptive invitation to join Pentecost’s Resurrection Movement. Now, as much as ever, we are in a “fear not” moment. Wait a week—Pentecostal power, with its assault on earth’s beleaguered condition and seemingly endless walls of hostility, is coming. Babel’s confused tongues, nationalist claims, conflicting cultures, and racial enmity are being reversed.

Lord, send the old-time pow’r.[4]

# # #

Endnotes

[1] Ken Sehested, “Patriotic holidays in the US: The nation’s liturgical calendar celebrating our militarized history,” prayer&politiks.

[2] For more historical background, see Ken Sehested, “Memorial Day: A historical summary,” prayer&politiks.

[3] See Campbell Robertson, “Birthplace of memorial Day? That Depends Where You’re From,” New York Times.

[4] From the hymn’s refrain, “Pentecostal Power,” by Charles H. Gabriel.