by Ken Sehested

“For truly, God laughs and plays.”

—Meister Eckhart

I played the game for 13 years, beginning in grade school, and enjoyed watching for many more after that. American style football (what we call soccer is known everywhere else in the world as football) is as choreographed as any ballet performance. Except when the ball is snapped, it turns into something like an after-hours jazz band jam, with improvisation by 22 different players. As such, it can get ugly; but when done with the skill shaped by disciplined practice, it is a thing of beauty.

It’s never been safe, of course. No sport is. For that matter, no part of life is risk free. Over 30,000 people die from car  accidents every year in this country. When was the last time you thought, before heading to the grocery store, “I wonder if it’s worth the risk?”

accidents every year in this country. When was the last time you thought, before heading to the grocery store, “I wonder if it’s worth the risk?”

But the beauty of the game is now overshadowed by its beastly afterword. We now know, definitively, that repeated blows to the head likely cause long term brain injuries.

Right: The author, 1968, attempting an intimidating pose.

It’s called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), “a progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in people with a history of repetitive brain trauma (often athletes), including symptomatic concussions as well as asymptomatic subconcussive hits to the head that do not cause symptoms.” Members of the military exposed to the concussion of bombs are also at risk.

It’s time to have an adult conversation about risk. It won’t be easy, or accomplished quickly. Other sports are also guilty, yes; we’ll get to them in time. For now, let’s focus.

§ § §

It was the first football game of my senior year of high school. We traveled west-by-northwest, paralleling the Louisiana coastline, to New Iberia, near where that bottle of spicy Tabasco sauce in your kitchen cabinet was made.

Sometime during the first half I was knocked silly, though I was still on my feet. All I remember is that I regained consciousness at halftime, sitting in the visiting team locker room. My teammates were milling around gulping water. One of my coaches stooped low and said something like: “Are you about ready to rejoin us, Sehested?”

I suddenly became aware that I had been mumbling to myself, over and over again, the familiar line from John’s Gospel, the preeminent text in my revivalist rearing: For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life (3:16). It was as if I were chanting a mantra—something, anything, to bring me back to consciousness.

This was the second of a half-dozen concussions, though I didn’t temporarily lose sensibility in the others. I was merely dazed, seeing my surroundings as though looking through a child’s toy binoculars turned backward, everything seeming to be at a distance. We called it “getting your bell rung.”

As far back as 2004 Virginia Tech researches documented the impact of head collisions in a football game, noting that it was the equivalent of a car wreck every week.

§ § §

Being playful is not the same as being distracted, lighthearted, nonchalant, or indolent. Play can also be intense, demanding, sweaty, but is always refreshing. Creativity, wrote the psychologist Abraham Maslow, is purposeful play.

One of my great regrets is that I associate running with punishment. In high school, during the week following a football game loss, we ran extra wind sprints at the end of practice. But if you give me a frisbee, an open field, and a play partner, I will literally run until my legs give out.

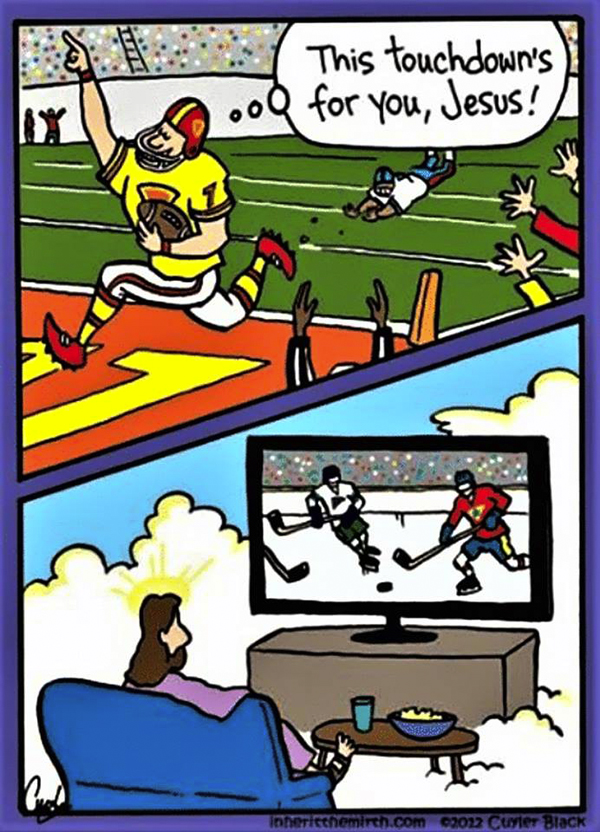

Play in this larger sense is most certainly a form of godliness. To be playful is to participate in transcendence, to be elevated beyond productivity demands, to be freed of indebtedness. Which is why the jubilee year, including the release from literal debt and slavery, is the Older Testament’s vision for creation’s destiny, a destiny echoed in the famous prayer Jesus taught his disciples: “Forgive us our debts. . . .”

In this sense, play is delight. In the Genesis story of creation, the crowning moment was sabbath, God’s resting and  declaration that all that had been made was “good.” The English word fails to capture the full range of the Hebrew word used, which is much more like “and God said it is delightful.”

declaration that all that had been made was “good.” The English word fails to capture the full range of the Hebrew word used, which is much more like “and God said it is delightful.”

Sabbath rest is playful rest, is luxuriating in delight, is being caught up in rapture. As such, sabbath is not merely subsequent to the labor of creation—it is an indication of creation’s character, its stamp of approval.

We ritually practice sabbath every seven days not because God enjoys our inconvenience or demands a little grim regard. The practice is training for how to spot God’s delightful presence during the other six days.

As French philosopher and Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chadin put it, “Joy is the most infallible sign of the presence of God.” Participating in God’s relishing of the world is the very thing that sustains us in and through the world’s suffering.

§ § §

I don’t know when my doubts began. I suspect my first hint that something was askew was when my junior high school football coach yelled at me: “I need you to get mad. You play better when you’re mad.” Conscious admission didn’t occur until the fall of my freshman year in college.

I wasn’t a great player, but I did get to choose between four different universities who offered me a scholarship in exchange for my gridiron play. I chose Baylor because of its religious offerings and in light of my pastoral career goal.

The fall of 1969 was not an auspicious season for Baylor football. We didn’t win a game, the only time that’s happened in school history. It would be decades before the glory days arrived for the school’s players and fans. That glory later lost its luster when a history of alleged sexual assaults by football players came to light—over 50, by 30 different players between 2011-2014.

The coincidence of sanctioned violence and sexual assault has long been a thing. I remember the comment a TV sports announcer made in 2015 during the collegiate football national championship game. After one particularly brutal tackle, the announcer said with much enthusiasm, “Now there’s a player with a big heart and no conscience.” He meant it as a compliment.

Shortly before the Christmas break I set an early morning appointment to speak with one of Baylor’s assistant coaches, the man who recruited me, to tell him I was considering giving up my scholarship. Before the meeting I rose before dawn, drove to a park on the edge of town, and parked my car on a bluff overlooking the Brazos River.

Given the anxiety I was feeling, you would think I was considering jumping; and in a way, I was—an identity suicide. What kept going through my mind was returning home for the Christmas break, going to my barber, who would ask “How’s the team doing?” to which I would reply, “I quit.” I imagined him taking his straight razor and putting it to my throat. In my culture, “quitter” was an adjective just slightly less disreputable that “communist.”

On top of this fear was the dumbfounded reaction of my parents. A lower working class family, who scrimped, penny-pinched, and borrowed like crazy to support my sister’s college education, here I was giving up a free ride. For what? I didn’t have an answer.

It wasn’t the “0-for” season that drained my enthusiasm for football. The university atmosphere, small and parochial as it may have been, was cosmopolitan to me. My scholarship came with virtual year-round time demands. Experiencing a larger world proved more compelling, even though I couldn’t say why.

§ § §

Last I heard, I still hold my high school record for the discus throw as a member of the track and field team. I played everything, one sport’s season melding into the next with hardly a break.

Sports taught me a lot about a great many important things. Learning to play as a team. Testing mental, emotional, as well as physical endurance and finding out that you had more than you thought. The exhilaration of a certain kind of exhaustion. Handling defeat but still coming back for more. Discovering the sheer intensity of relationships with  teammates born of shared ordeal. Coming to recognize the irony that freedom of fluid movement comes by disciplined, repetitive, demanding practice. Realizing that getting up again is a coup against being knocked down.

teammates born of shared ordeal. Coming to recognize the irony that freedom of fluid movement comes by disciplined, repetitive, demanding practice. Realizing that getting up again is a coup against being knocked down.

Thus I speak as a devotee when I say we must begin dismantling the sport of football.

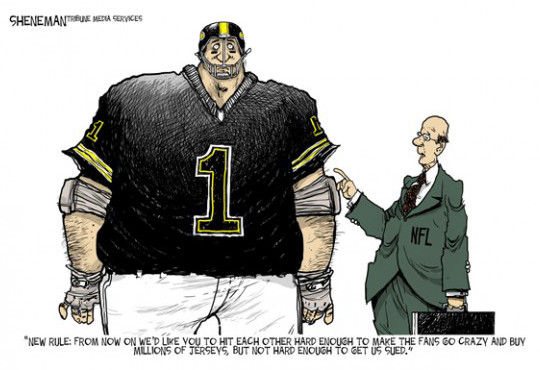

Lord knows it won’t be easy. The National Football League (NFL) projects its 2017 revenue at $14 billion, with plans to increase that to $25 billion in the next decade. The scale of star players’ salaries, combined with product endorsements, has broken the $50 million per year mark. The NFL commissioner commands $31 million annual salary, probably to be raised to $49 million in the coming year. The coaches of major college football programs make four, five, six times as much as school presidents, 10-20 times as much as full professors, and the football revenue in some schools pays for a lot of other things—not to mention the shared identity factor for more than a few alumni/ae donors.

In other words, a lot of people make a lot of money in and around the game at almost every level. Abolitionists will be branded as killjoys—even treasonous, or heretical, or fiscally irresponsible.

The strategy for addressing the carnage of this sport—like the strategies for most effective movements for social change—won’t begin at the top. Calling for an NFL or college football program boycott would be foolhardy. Rather, the squeeze needs to start at the lower end. Recently several former NFL star players called for a ban of football for those under 14. Now a Maryland lawmaker has submitted legislation to this effect. These initiatives will surely grow. Add the weight of your conviction to these efforts.

The recent time out strategy behind implementing the “concussion protocol” in football, along with severe penalties for certain head-to-head collisions, are delaying tactics. The ballooning size of players, speed of the game, and lengthening season simply preclude any meaningful measures to reduce the risk of severe injury. Think Isaac Newton’s Second Law of Motion: Force equals mass times velocity. The human body was not meant to withstand such fury.

It is a hopeful sign that numerous pros are publicly weighing the risks. Last year a prominent sports commentator, himself a NFL veteran, abandoned his six-figure salary, saying he could no longer in good conscience promote the sport. There will be more defectors.

Sure, I love cooperative games as much as competitive ones. I was raised as a “free range” kid long before the phrase was invented, and parented as such as well. But there is a limit to every laissez-faire posture. Football has crossed it. The beastliness outweighs the beauty. This demands an intervention.

Who’s with me?

# # #